Blog Archives

Are You a Teacher or Just a Lecturer?

Teaching Is Not Just Another Job

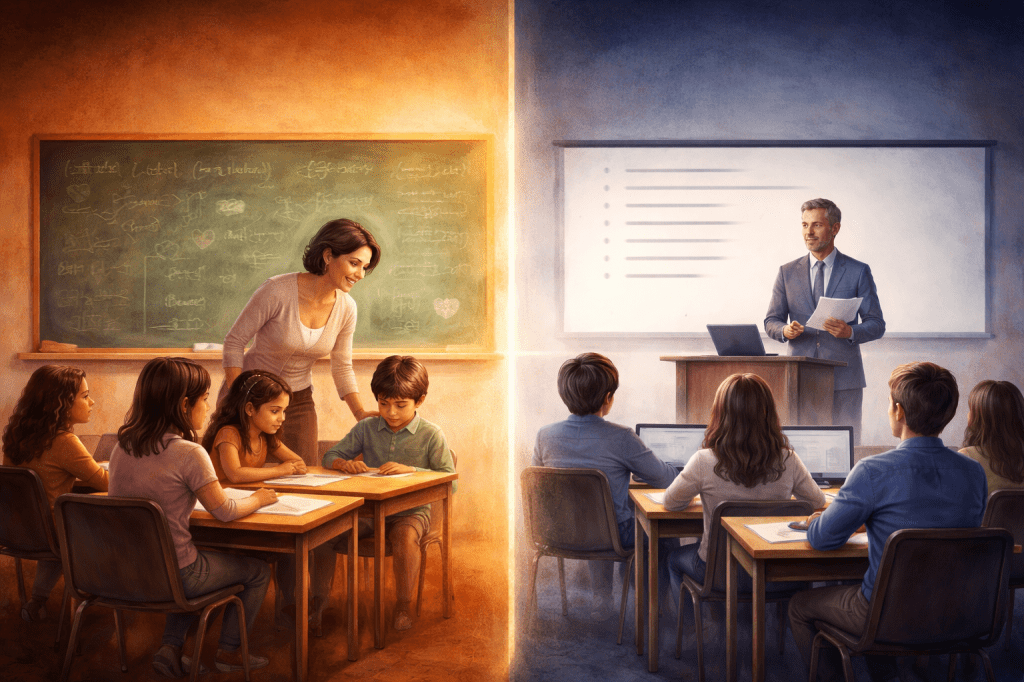

No two people who stand in front of a classroom practice teaching in exactly the same way. Some see it primarily as a task of delivering content; others see it as a responsibility to shape minds, attitudes, and lives. Titles may be the same, but intentions, mindsets, and commitments often are not. This raises a question that is uncomfortable yet necessary—not to accuse, but to reflect: Are you a teacher, or are you merely a lecturer?

No two teachers view teaching as a profession through the same lens. They do not share the same set of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values either. Like fingerprints, their mindsets, tendencies, and personal qualities are unlikely to be identical.

Even if teachers are forced to use a similar lens, they would still see their job differently. They have educational and personal perspectives that are uniquely theirs—or, in some cases, none at all.

When given the same course syllabus, we should not expect teachers to map out their daily lesson plans in the same manner. They design learning activities and implement them as they see fit. Some, unfortunately, do not bother to plan at all.

Teachers’ work attitudes also differ.

There are those who are highly conscious of the number of hours stipulated in their contracts. You cannot expect them to work overtime or do extra work unless you provide additional compensation.

Conversely, there are teachers who are willing to go the extra mile. They assist students beyond assigned teaching hours, volunteer for tasks, and do things not written in their job description—expecting nothing in return.

Perhaps the most damaging are teachers who arrive late to class or leave early. For reasons only they know, they do not perform their assigned tasks the way they ought to. Required paperwork is submitted late—or not at all.

If you are a teacher reading this, here is a question: Which of the three groups do you belong to? First, second, or third? Of course, only you know. No one can force you to be in the second group, but at the very least, stay away from the third group.

There are also teachers who are eternal fault-finders—always trying to identify something wrong, whether with policies, colleagues, or administrators. And when they succeed, they either whine about it, gossip about it, or do both.

Teachers also differ in the way they treat their students.

Some set standards that are difficult to achieve, while others know how to calibrate expectations so even the slowest learners have a chance to succeed. There are teachers who believe in a “one-size-fits-all” approach, assuming that teaching and learning processes are standardized and cannot be adjusted. Conversely, there are teachers who understand that students differ in learning styles, abilities, and personal backgrounds. They recognize these differences and differentiate their methods accordingly. These teachers do not believe that standards are absolute.

At its core, the differences among teachers may be summarized as follows:

- There are teachers who possess both passion and compassion.

- There are teachers who have only one of the two.

- There are teachers who have neither.

And again, if you are a teacher reading this, ask yourself: Which of these describes you?

If it is the third, you might be in the wrong profession. Think about it.

Now, let us ask why teachers are different.

Why do teachers approach their profession differently?

Why do they exhibit different work attitudes?

Why are some passionate and compassionate, while others are not?

For clarity, teaching performance is often reduced to a single outcome: effective or ineffective. Work attitude is seen as good or bad. Students’ treatment is viewed as fair or poor.

What causes teachers to treat students the way they do? Some are perceived as mean, unfair, or inconsiderate. Is this rooted in upbringing? Life experiences? Or perhaps they were treated the same way by their former teachers and came to believe such behavior is normal?

Sometimes, what appears to be indifference or harshness is actually exhaustion. Burnout does not excuse poor teaching—but it does help explain why some teachers gradually lose the fire they once had.

Teachers need to be reminded of the importance of building strong rapport with students. Numerous studies show that among the most valued qualities of effective teachers, as perceived by students, are the ability to build relationships and a patient, caring, and kind personality.

As Andrew Johnson aptly puts it:

“Teaching starts with a relationship. Until then, you are just a dancing monkey standing in front of your students performing tricks.”

One of the gravest mistakes school authorities can make is hiring a “nonteacher” to teach. In some schools, individuals teach despite having no education degree or formal teacher training. They may have been hired for reasons known only to those who approved them.

How can someone be effective and passionate in a profession that is completely alien to them?

To be fair, there are rare exceptions—individuals who compensate for the lack of formal training through humility, mentorship, and continuous learning. But these are exceptions, not the rule.

Being a math wizard does not automatically qualify one to teach math. Having perfect pronunciation and impeccable grammar does not make one an English teacher. Knowing a subject does not mean one can teach it.

Teaching requires pedagogical training: setting objectives, selecting appropriate strategies, motivating learners, and designing assessments that genuinely measure learning.

Do we really think that teaching is just another job?

Are you a teacher or merely a lecturer?

A lecturer delivers content; a teacher shapes minds. A lecturer measures success by how much material is covered, while a teacher measures it by how much learning actually happens. Lecturers speak; teachers listen. Lecturers are satisfied when a lesson ends on time; teachers are concerned about what remains unclear after the bell rings. Teaching goes beyond explaining concepts—it involves understanding learners, adjusting methods, and taking responsibility for whether learning takes place. All teachers lecture at times, but not all who lecture truly teach.

How can someone with no grounding in pedagogy fully understand the work ethic required of teachers—or agree with the idea that teaching is an act of self-sacrifice undertaken for the greater good?

When teachers fail to perform or behave as expected, examining their academic and professional background may provide insight. They may not have been trained as teachers at all.

But a more troubling question remains: Why are there teachers who were trained to teach, yet behave as though they were not?

Teachers’ actions are shaped by the personal educational philosophy they develop as they study various theories and “isms” during their training. This philosophy evolves through experience. Their decisions are also influenced by personal belief systems and the colleagues they choose to surround themselves with.

The way teachers behave, speak, and conduct themselves reflects their educational philosophy—or the absence of one. Professional conduct depends on whether they adhere to the code of teacher professionalism.

When teachers act or speak inappropriately, it may be because they are unaware such a code exists—or because they choose to ignore it.

Even without formal awareness of such a code, common sense should remind teachers to be careful with their words and actions. Otherwise, they risk being charged with conduct unbecoming of a teacher.

That is, if they care—if teaching is still a calling, and not merely a paycheck.